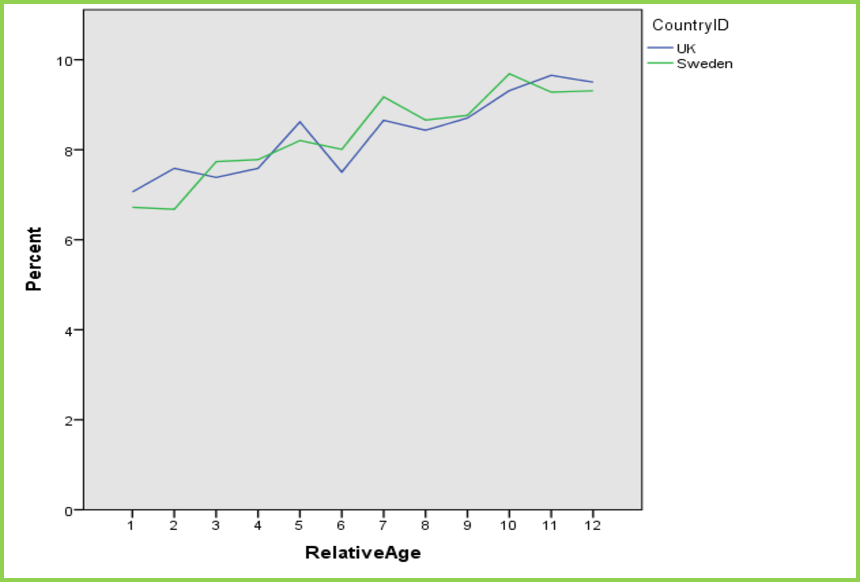

It has long been recognized that the oldest children in age-based cohorts tend to outperform and have better mental health outcomes than their younger-aged peers. While younger children may appear more hyperactive, impulsive, and/or inattentive than older children, this may be because of their age-related immaturity. Research has shown that late birthdate is associated with an increased risk of being diagnosed with and medicated for ADHD.

Simon Kitson is an Educational Psychologist based in Bristol who specializes in working with children with ADHD and Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Professor Michael Fleming from the University of Glasgow, said:

As a child born in July with a brother born in August, I was always well aware of the differences between myself and my Autumn-born peers. Back then they seemed bigger, more capable, and more prepared for school. as an adult, it’s clear that such a small age gap makes little difference in developmental terms. Yet children in Reception (Kindergarten in the US) may feel their peers have abilities that they do not yet share.

As a child born in July with a brother born in August, I was always well aware of the differences between myself and my Autumn-born peers. Back then they seemed bigger, more capable, and more prepared for school. as an adult, it’s clear that such a small age gap makes little difference in developmental terms. Yet children in Reception (Kindergarten in the US) may feel their peers have abilities that they do not yet share.

How does age influence ADHD diagnosis in children?

Many experienced reception/kindergarten educators are aware of this relationship between age and ability. The variation in attention of young children can be misleading to adults who work with them. Rather than indicating a disorder, these differences represent the normal variation in the early years population. Where there are concerns, objective ADHD testing with QbTest or QbCheck is useful to clarify age-related differences.

Attention span by age

- Age 4: 8-12 minutes

- Age 5: 10-14 minutes

- Age 6: 12-18 minutes

- Age 7: 14-21 minutes

- Age 8: 16-24 minutes

- Age 9: 18-27 minutes

- Age 10: 20-30 minutes

As Mahone and Schneider observed:

“Most often, though, inattention is a normal variation observed in typical preschool child development, making identification of “disordered” attention more problematic (Mahone, 2005), especially given the tremendous variability in caregiver ratings of attention and endorsed symptoms of ADHD in this age group.”

In the UK, children normally start their reception class year when they are four years old, and turn five during. Table 1 indicates the potential age-related differences between children that would be observed in a typical classroom at this age.

A 2017 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research indicated an advantage for children who entered school at an older age. A 2019 study further indicated that older children have better odds of attending college and graduating from an elite institution.

Developmental differences in age

When it comes to identifying potential ADHD, classmate comparisons are problematic as pupils in the same school year vary in age by 12 months. The youngest children in a school year are significantly more likely to be referred for assessment, receive a diagnosis, and be treated for ADHD than those who are up to 12 months older.

At Qbtech, we compared the numbers of QbTests performed in children young for their school year with those who were older and found that younger children are tested 37% more – which is strongly supportive of the findings above.

These children may simply be displaying signs of relative immaturity, resulting in referral bias and increasing the risk of over-diagnosis.

QbTest can be administered to a child as young as 6 years old. Reports are generated by comparing an individual’s results with benchmark data from people of the same gender and age without ADHD, removing age and gender bias and reducing the risk for over and under-diagnosing ADHD.